For over a decade, angel tax has been one of the most debated and controversial elements of India’s startup policy framework. Introduced as a measure to curb the circulation of unaccounted money, it gradually evolved into a major pain point for early-stage startups and angel investors, often creating uncertainty at the very moment when young companies were most in need of risk capital. With recent policy changes and the eventual abolition of the provision, angel tax has entered a transitional phase, making it essential for founders and investors to clearly understand how it worked, what exemptions existed, and what filing procedures still matter for past investments.

Angel tax originated from provisions in the Income-tax Act that empowered tax authorities to scrutinise share premiums received by unlisted companies. When a startup issued shares at a price higher than what tax authorities deemed to be its fair market value, the excess amount was treated as income and taxed accordingly. The logic behind this approach was rooted in anti-abuse concerns. Policymakers feared that shell companies could raise money at artificially inflated valuations to launder black money under the guise of legitimate investment. While the intent was regulatory discipline, its application to genuine startups produced unintended consequences.

Early-stage companies rarely have predictable revenues or stable cash flows. Their valuations are typically based on future potential, intellectual property, market opportunity, or the credibility of the founding team. Angel investors, who often invest at the idea or prototype stage, price this risk into their investments. However, these forward-looking valuations frequently clashed with tax officers’ more conservative assessment models, leading to disputes, prolonged scrutiny, and retrospective tax demands. For many startups, the tax notice arrived years after the investment was made, long after the capital had been deployed into product development or market expansion.

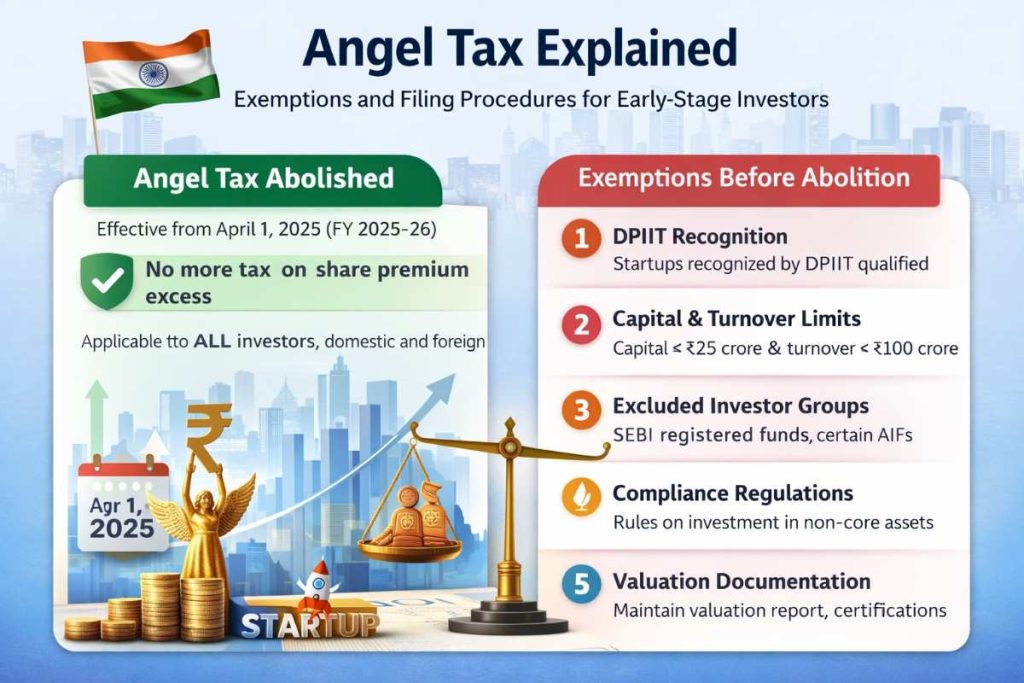

To soften the impact, the government gradually introduced a framework of exemptions designed to protect genuine startups while preserving safeguards against misuse. A key pillar of this framework was official recognition as a startup by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade. Once recognised, eligible startups could apply for exemption from angel tax, provided they met certain conditions relating to age, turnover, and nature of business. This recognition served as a signal that the enterprise was innovation-driven and not a vehicle for financial manipulation.

Another important condition related to the total amount of capital raised. Startups were required to ensure that their paid-up share capital and share premium, after issuing new shares, remained within a prescribed threshold. This cap was intended to distinguish early-stage ventures from more mature companies that might otherwise misuse the exemption route. Additionally, turnover limits were imposed so that only relatively young and small enterprises benefited from angel tax relief.

The exemption framework also took into account the profile of investors. Investments received from certain categories of regulated entities, such as registered venture capital funds and alternative investment funds, were treated differently, as these investors were already subject to oversight under financial market regulations. Over time, specific relaxations were also extended to certain non-resident investors, although this area remained complex and often required careful structuring and legal advice.

Alongside eligibility conditions, compliance requirements played a central role. Startups seeking exemption were expected to maintain detailed valuation reports prepared using prescribed methods. These valuations had to be supported by documentation from merchant bankers or qualified professionals, outlining the assumptions and methodologies used to arrive at the share price. Declarations and filings had to be made within stipulated timelines, and startups were required to adhere to restrictions on how the raised funds could be deployed, particularly with respect to investments in non-core assets.

Despite these safeguards, uncertainty persisted. Many founders argued that the fear of future scrutiny had a chilling effect on angel investment, especially from individual investors who lacked the legal resources to navigate prolonged tax disputes. Over time, industry bodies and investor groups consistently called for a more fundamental solution rather than incremental exemptions.

That solution arrived with the government’s decision to abolish angel tax altogether for investments made from the financial year 2025–26 onward. The removal of the provision marked a significant shift in regulatory thinking, signalling greater trust in market-driven valuations and a recognition of startups as engines of innovation and employment. With this change, the question of taxing share premiums for unlisted startups has effectively been put to rest for future transactions.

However, the end of angel tax does not automatically erase the past. Investments made in earlier years remain subject to the legal framework that existed at the time. For startups and early-stage investors involved in funding rounds prior to the abolition, compliance and record-keeping continue to matter. Valuation reports, shareholder agreements, recognition certificates, and correspondence with tax authorities must be preserved to address any ongoing assessments or appeals. Transitional clarity is especially important for companies that raised capital close to the cutoff period or are still facing unresolved scrutiny.

For early-stage investors, the broader implication is a more predictable and founder-friendly investment climate. The abolition reduces regulatory risk and simplifies decision-making, allowing angels to focus on mentoring and scaling startups rather than navigating tax uncertainty. For founders, it removes a major psychological and financial burden, enabling them to raise capital based on business merit rather than defensive valuation strategies.

Angel tax, once emblematic of the friction between regulation and innovation, now stands as a lesson in policy evolution. Its phased exemptions and eventual removal reflect how regulatory frameworks can adapt in response to ecosystem feedback. As India positions itself as a global startup hub, the transition away from angel tax is likely to be remembered as a turning point that restored confidence in early-stage investing and reaffirmed the role of entrepreneurship in economic growth.

Add businesssaga.in as preferred source on google – Click Here

Last Updated on: Monday, February 2, 2026 3:46 pm by BUSINESS SAGA TEAM | Published by: BUSINESS SAGA TEAM on Monday, February 2, 2026 3:46 pm | News Categories: Business Saga News, Business News Today, Trending News

Leave a Reply